Dragons and Reasoned Fantasy...

Dracontology – A

Modern Synthesis

The study of dragons as creatures is almost as old as man itself. The confusing anatomy of many dragon species has resulted in confusion as to their taxonomy and evolution. Phylogenetics and evo-devo may provide a better perspective than classical purely anatomical approaches.

The Enigma of Dragon Limbs –

Dragons of various sorts can have as many as 8, or as few as 0 limbs, standard Western Dragons have 6, including legs and wings, while Wyverns have a more typical bird-like arrangement of a single pair of wings and 1 pair of hind-legs.

Dragons can be typically broken down into a few groups, but there are many specialized forms and outliers.

Basilisks – These have 8 legs.

Tarrasques and Hexadragons – These have 6 legs.

Western Dragons – These have 4 legs and one pair of wings. This is the only group known to breathe fire.

Drakes – These have 4 legs and no wings.

Long/Eastern Dragon – These have four legs, no wings, but also have a serpentine body, unlike most Drakes.

Wyverns – These have a single pair of wings, and long hind limbs.

Knuckers – These have 1 pair of forelimbs and 1 pair of wings.

Linnorms – These have no wings, and one pair of forelimbs.

Wurms and Orms – These have no limbs or wings at all.

Flying Serpents – These have wings but no legs.

Four-winged Snakes – These have 2 pairs of wings and no legs.

Molecular studies and shared anatomical and biochemical features confirm that these are all truly dragons, so they must share a common ancestor, but how? And why is there so much variation in the number of limbs?

The Dracothyris model, a Draconic common ancestor –

A common rule of vertebrate evolution is that it is easier to lose a physical structure, than it is to re-evolve it once it has atrophied. Such an example is the snake or the legless lizard, it was easy for them to lose all four limbs, but none have re-evolved functional limbs from this atrophied state.

So what does this tell us? Put simply, we can begin to arrange Draconic phylogeny with limb loss as a trajectory. Eight legged Basilisks are the most stemward, primitive form, and Wurms, who have lost limbs entirely, are the most advanced, derived forms. Limb loss and the evolution of wings from limbs are both trends in Dragon macroevolution.

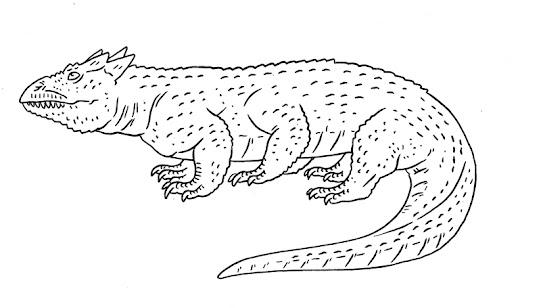

This brings us to the question, what was the common ancestor of all Dragons? Such a thing has not been found in the fossil record. It seems that the amniote and reptile-like features of dragons may be convergent, and that indeed, its distant ancestor must have been a tetrapod-like fish, or another kind of fish, with 4 pairs of fins. The first true member of the Dragon group, one that breathes air, has keratinized scales, and many other amniote-like features, we can call Dracothyris. It would have been a roughly lizard-shaped animal, with 4 pairs of sprawling legs, but besides this may have roughly resembled early sauropsids and amniotes such as Hylonomus.

From this founding ancestor, we can get all known kinds of modern dragon. Different configurations of wings and limbs, and the trait of losing pairs of limbs, being a characteristic of the group. Other characteristics include horny or bony scales that can often serve as armour, cranial horns or crests with a bony core, and a lizard-like dorsal ridge, many kinds of dragons have also evolved an opposing hind toe on back feet, front feet, or both.

With this well-supported model of Dragon evolution, we can propose a phylogeny

like this:

Basilisks diverge first, giving rise to the typical,

venomous Basilisk, and later the 8-flippered Scolopendra of the China Sea and

Diverging next we have Hexadragons such as the Whowie, and armored forms like the Tarrasque. These have 6 legs.

Next we have the group containing 4 legged dragons that possess wings, the “Noble Dragons”. Including the Western Dragons such as the Welsh Red Dragon, Dragonet, and Asdeev. The Piasa is also a member of this group, which seems to have diverged before a more upright stance evolved.

Some kinds of noble dragon lost their forelegs

and favored a bipedal, bird-like stance, these are the Wyverns.

The common ancestor of this group also diverges into the Drake group, which lose their wings, but retain an upright stance; these include Mushussu, Drake, and Quilin.

Arising separately, from primitive six-leggers are the 4 legged dragons, primitive members of this group are lizard shaped, such as the Salamander and Gowrow.

Diverging from this are the Long group, including typical Eastern Longs as well as other legged serpents like Ninki-nanka and Nguma-monene.

Primitive six-limbed dragons close to the split between Hexadragons and Noble Dragons, then gave rise to a collective group of serpentine dragons that vary in limb arrangements.

Knuckers lose their hind limbs, thus posessing small wings, and powerful forelimbs, the Jaculus is a kind of primitive Knucker that has large wings and is a competent flier.

Their relative, the Chinese 4 Winged Snake, turns the forelimbs into a second pair of wings.

Their common ancestor also diverged into the Linnorm group, which have only forelimbs, no wings or hind limbs at all. Being generally aquatic,

Linnorms also give rise to Marine forms, with flippered forelimbs, such as the Persean Ketos.

The common ancestor of these 3 groups also gave rise to Flying Serpents, also known as Amphipteres, retaining wings but losing their forelimbs.

The Quetzalcoatl is an interesting kind of Amphiptere that has developed fine, feather-like filaments covering its body, which are brightly colored.

Diverging somewhere near the stem of all of these, are Wurms, Orms and Drakon, which merely resemble giant horned snakes, having no limbs.

The mystery of multi-headed dragons, an Evo-Devo approach –

This leads us to another question. Some dragons have three or more heads, how does this fit within the paradigm? The answer comes from embryology and evo-devo. Dragons as a group possess a unique developmental quirk, which allows conjoined, mutant dragons, ones born with more than one head, to survive well into adulthood and thrive. This trait may exist as a survival strategy, but what triggers it is unknown. What we do know is that the extra heads, as many as 8, are functional, and share nutrients with the rest of the body, including what they consume. This phenomenon has been termed “Symbiotic Twin Polycephaly”. No new species have arisen with this trait, as it is comparably rare, but certain species tend to produce such mutants, that are commonly given other names. Western Dragons with more than 3 heads are called Zmey Gornych by the Russians, and 3 headed Drakes can be called Cerberus in Greek antiquity, as are many-headed Linnorms, which they call Hydra. Japanese Linnorms of large size with 8 heads are referred to as Orochi.

Thus, we see that these fortunate singletons are a kind of beneficial variation, a polymorphism in their phenotype, as opposed to true species or genera of Dragon.

What is a dragon and what is not? The paradigm of “False Dragons” –

Many animals exist in this world which may be considered dragons by some, but strictly are their own kind of animal, unrelated to true dragons. These include:

Burrunjor and Gauarge – Bipedal meat-eating dinosaurs (Theropoda).

Water-horse/Nessie – Relictual Plesiosaurs (Plesiosauria).

Sea Dragons (Leviathan, Heraclean Ketos etc) – 4 flippered marine saurians (Mosasauria).

Sachamama – Seemingly serpentine with short webbed feet and a large ornate shell, a turtle (Pleurodira).

Carp Dragon – Same as Shachihoko, large ferocious carp-shaped fish with big sharp teeth (Perchiformes).

Pyralis – Wasp-like insect which is attracted to flames, often mistaken for a tiny dragon (Hymenoptera).

Amphisbaena -large serpentine burrower which appears to have a head on both ends (Amphisbaenia).

Peluda – Large, dragon-faced quadruped which has thick shaggy fur and large quills (Cynodontia).

Banib and Geelong Bunyip – Scaly Dinosaurian biped with a large serrated bill and powerful arms (Iguanodontia).

Blenkige Dragon etc – Broad headed crawling quadruped with a furry neck and finned tail, a giant Amphibian (Caudata).

Taniwha – Giant freshwater crocodile, cold tolerant (Mekosuchinae).

Crocodile-snake – Giant limbless lizard that is short and fat (Cordylidae).

Snallygaster, Kongamato, Thunderbird, Ropen – Large, short-tailed pterosaurs with cranial crests and teeth. (Pterodactyloidea).

Mokele-mbembe – Mid sized sauropod dinosaur with some semi-aquatic habits (Lithostrotia).

Odontotyrannus – Large, robust dragon like beast with 3 horns, a dinosaur (Ceratopsidae).

Moho or Mo’o – Giant semi-aquatic terror skink commonly

found in

All of these animals have some traits convergently in common with true dragons, but none of them qualify as true dragons biologically.

Dragonfire – The breath weapon of the Noble Dragons

Draconic breath-weapons do not only include fire. Some dragons, such as Gargoulle or Emperor Long may spit streams of pressurized water, or breathe heavy vapour. Wyverns are known to spit venom in the way a cobra does, and the Cockatrice, a type of Wyvern, has a venomous bite. Some kinds of Wyvern are also known to produce toxic gases from their stomach as a breath weapon.

But where does this leave the Noble Dragons, especially the Great Wsetern Dragons of Europe? The smaller Dragonet is able to spit 2 streams of chemicals that combine to form a scalding hot, poisonous breath weapon, and this seems to be the primitive state that the common ancestor of all Great Western Dragons had. A large western Dragon such as a Russian Black or Welsh Red, produces 2 kinds of volatile chemical which are stored in separate pouches in the throat, ejected quickly at once in a long stream, they make contact with each other in the air, and become a napalm-like, devastating column of flame. When inside the body, these chemicals are kept separate, and it is only by careful coordination as it spits, that the 2 streams cross as they are ejected, and become a flame, via a chemical reaction that initiates combustion. Young dragons take a long time to perfect this coordinated action, and some unfortunate young ones may combine the chemicals within the mouth and blow their own heads off.

Conclusion – More than a Myth

Dragons have featured in legends since time immemorial, and are rare in being a creature that is simultaneously both real and mythical at once. It is only in the light of modern scientific techniques, that the Dragons make any sense beyond the legends that we all know.

All images, designs and writing on this blog are the property of Timothy Donald Morris, do not use, reproduce, or copy them without my permission.

© Timothy Donald Morris 2022

Comments

Post a Comment