Special Mini-project - The Last Biosphere

I have often wondered about life on our planet, many hundreds of millions of years into the future, when the earth's biosphere is in its dying days. I decided to create a project centered around this, taking influence from a couple of my other projects, and the general opinions of other artists as to how this might be.

_

The Last Bioshphere

It is over 600 million years in the future, the light of the ageing sun is so intense as to render much of the now unrecognizable continents, into parched rocky deserts of blazing heat. The oceans and fresh water bodies are slowly but surely evaporating into smaller shallow basins, so briny and warm as to also be fairly hostile.

The Sparse Terrestrial Ecosystem - On land, most living things are concentrated closer to the poles, or at higher elevations, where temperatures and evaporation levels are a little lower. Low rocky ridges or drifts of sand and grit form the substrate on which the rarefied vegetation of this region grows. Areas of shade are sought out by the small arthropods and vertebrates that live here, and many build their nests in tunnels or burrows to escape the relentless heat.

Photosynthesis as we largely know it is impaired by the age and intensity of our sun. Most remaining plants are C4 photosythhesizers descended from herbs like Sorghum, though few resemble this ancestral form now.

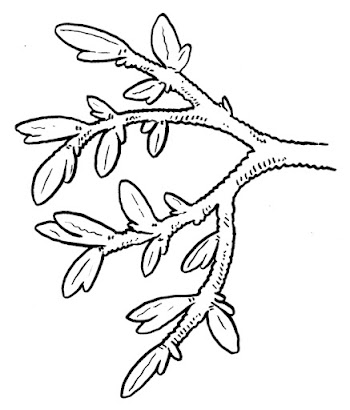

Another common desert plant is this small bush, which grows abundant absorbent fibres amongst a brace of spiky succulent leaves. This fuzzy appearance allows it to trap and imbibe any moisture from the air, or from the rare mist and damp that settles during the colder nights.

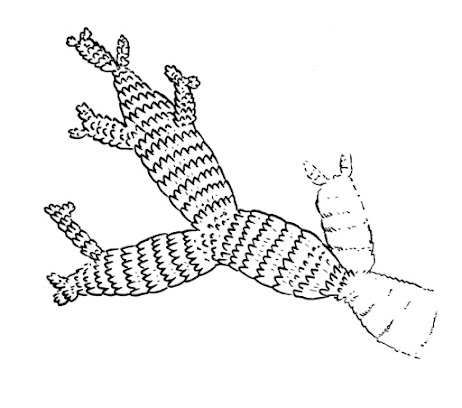

Feeding on this rare vegetative growth are various tough, resilient insects, such as this descendant of the weevil. It furtively ranges across the ground in search of healthy plants that it can drill into with its mouth-parts, in order to feed, also eagerly consuming nectar and seeds in the fruiting season. It lacks wings, and its abdomen is covered by fused, silvery elytra that reflect the rays of the sun to avoid desiccation.

Feeding on beetles such as these, are a range of small predators, in fact all animal life here remains under 10 centimetres long, as water and food are too scarce to sustain anything larger. The largest predator is this squamate, covered in a heavy coat of broad horny scales, which serve to protect it from sun damage, and from losing water. Though resembling a lizard, it is about as distant taxonomically from its lizard ancestors, as a hummingbird is from a crocodile. Its teeth have fused with its jaw, and its whole face is covered in a sheath of keratin. This beast reaches only 10 centimetres long or less, but it is the apex predator of this ecosystem. Apart from various invertebrates, it will eagerly consume herbaceous succulents in order to obtain vital water.

There are spiders here too, similarly armoured to their beetle prey, their pedipalps form trenchant claws for grasping, and their abdomen is capped with a tough chitinous shell. This is the fastest predator in the ecosystem, and it can often strike its insect prey unawares. This speed also helps it seek areas of shade and moisture during the heat of the day.

As long as the first joint of a man's thumb, this agile flying beetle seeks prey and water by remaining almost constantly aloft, roaming far and wide with speed like a dragonfly. Insect and arachnid prey is captured with its barbed forelimbs, and its elytra are reduced.

In areas where mositure levels fluctuate less often, particularly in thickets of herbage, we find an unusual beast, a giant, thick-skinned tardigrade that may grow as long as 5 centimetres. Having chitinous teeth around its large, nozzle like mouth, it is a fierce predator of smaller invertebrates. Though when active it requires some small amount of moisture and shade, during hard times or long exposure, it can enter an altered desiccated hibernation until conditions improve, almost indefinitely.

As might be expected, with so few large animals, parasites are rare, but this 4 millimetre-long parasitoid wasp specialises in laying its eggs inside the tissues of other unsuspecting arthropods, which will eventually be eaten alive. The adult serves as an important pollinator of various desert plants, also.

Some places where sand, dust and grit, accumulate via wind action, form deep drifts that serve as the nest for this burrowing lizard, which reaches no more than 7.5 centimetres long. It tends to remain near the surface, in order to ambush arthropods of various sorts, but it will also scavenge dead insects, and commonly consumes parts of the root systems of desert herbs and succulents.

Unusually, descendants of mold and fungus take root here too, usually their mycelia spread a small distance underground, covered in a greasy wax-like substance that protects them from desiccation. Some terrestrial molds here grow fluffy outer coatings to absorb rare moisture like a sponge, while others are usually only apparent at the surface by their crusty or bulbous fruiting bodies, that sometimes serve as food for other creatures.

-

The Shallow Oceans- A significant portion of the earth's water has evaporated, and thus the sea levels are much lower, and consist of briny basins restricted to what was once the sea floor. In deeper areas of very low altitude, the temperature becomes too high for most complex life forms to proliferate, but in shallower basins, cyanobacterial mats and slicks of slimy algae coat the sea floor, providing a medium where a modest fauna tries to thrive.

Common here are large congested mats of cyanobacteria, and crusty calcified growths that resemble stromatolites, these provide shelter and food for various small animals.

Glass sponges of relatively small size may cluster in areas where light levels are too low for algal growth.

Strange stemmed filter-feeders, no longer than a man's hand, grow in areas where water-borne nutrients and larval plankton are higher in density, this is in fact a giant descendant of the rotifer.

Encrusting some rocky or crusty areas, these thumbnail-sized predatory rotifers snatch small arthropods and large plankton from the currents.

Where the sea floor is covered in soft algal slime, this somewhat carcinized, pinky-finger-sized shrimp takes refuge, when not feeding on the algae itself. It has keen vision in order to spot oncoming predators, and in order to drive away rivals.

Epifauna and slow-moving crustacea form the diet of one of the very last saltwater fish. This small, armoured descendant of horn-sharks barely looks like a shark at all, save for its fin spines. No bigger than a man's hand, it will also consume calcified cyanobacterial crusts when meatier prey is scarce.

This worm-like predator is commonly found lurking in sheltered areas, either in a shallow burrow or coiled around a snag or crack. As long as a man's middle-finger, this little raptorial beast is in fact descended from starfish.

Another echinoderm is this flat, soft-bodied urchin, which feeds mostly upon cyanobacterial mats.

And this echinoderm may resemble a fuzzy sea-cucumber, but is in fact another sea-star descendant, and indeed it usually feeds by processing bare patches of sand and silt.

This finger-sized, shrimp-like crustacean is a proficient swimmer, and uses its feathery limbs to gather edible nutrient particles and microorganisms from the briny water. It is in fact one of the most common free-swimming animals on the planet.

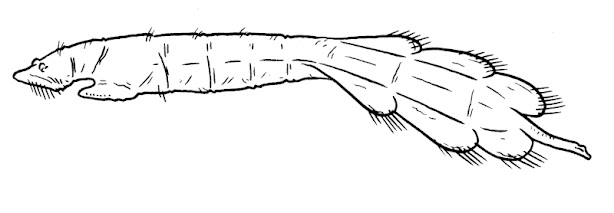

Another free-swimming animal is this unusual species of polychaete worm, which undulates is fin-like appendages in order to chase small arthropods which it snatches with its jawed proboscis. It is relatively large, as long as a man's hand.

The largest animal in the ocean, and indeed on earth, is this great soft-bodied crustacean, reaching up to a meter long. Propelling itself via powerful undulations of the pleopods along its muscular abdomen, it gathers water-borne nutrients, plankton and microorganisms with its shaggy forearms. When its arms are laden with food, it combs the food into its mouth with its inner 2 pairs of arms. Though its jointed limbs have fairly hard cuticles, and its head-shield is hardened in order to form a hydrodynamic body-shape, it is still vulnerable and soft compared to the crustaceans of our day.

In this extreme environment, the intertidal zone is even more ephemeral than usual. This 6 centimetre-long aquatic tardigrade prospers here, able to swim, burrow, and clamber about if it needs to, it can even survive being stranded and dried out upon the shore.

-

Salt-pan Lakes-These bodies of fresh water are even more extreme than the oceans, and do not provide drinking water for the surrounding terrestrial animals at all. Fauna here consists of various Halophilic small creatures, including tiny fish, insects and tardigrades which feed on abundant cyanobacterial slime.

As in the ocean, low crusty stromatolite-like growths of cyanobacteria can be found where the water is not too shallow.

A species of brine-loving fly is common here, so much so that they have achieved the ability to reproduce in their larval form. The flying adult form is still essential nonetheless, to spread the species to other areas, but when a large body of water is found, most larvae enter the stage where they become larger and can reproduce without maturing.

This thumbnail sized tardigrade prospers in ephemeral salt-pans, as it can survive desiccation for a long period, as most tardigrades can. When in its mobile stage underwater, it gets almost all of its food via the photosynthesis achieved by symbiotic cyanobacteria that grow in its tissues.

Along the shores and in the shallows, this crust-forming slime-mold is able to move from place to place, slowly feeding on algal slime. When conditions get too dry or hot, the crust that forms on its upper surface covers the whole animal, and congeals solid, until it is revived by adequate moisture or movement of the water on shore.

_

And thus these 3 ecosystems form the final biota of the animalia

and plants, though protista, cyanobacteria and other unicellular life

may persist longer. As the heat and evaporation worsen, life will

become virtually impossible, except for that of the extremophile,

which true animals and multicellular plants cannot hope to attain.

© Timothy Donald Morris 2024

Comments

Post a Comment